Nagendra Sharma

“All humans are equal,” said the Buddha and, by so doing, let loose a storm that, more than sending jitters down the spine of a traditional caste-ridden Hindu society, swept himself off his feet!

Hinduism stood for casteism and Buddha opposed it. It was nothing for the Buddha to partake of the food offered by Sujata, a lowly untouchable girl as far as the Hindu were concerned thereby drawing hordes of people of her ilk towards him, and away from Hinduism. What’s more, Hinduism was based on sacrifices and rituals; Buddha had no respect for them. Hindus believed in a transcendental soul; Buddha did not support this belief. Thus wasn’t Buddha against almost all the basic tenets of the then prevalent Hindu faith?

Obviously, Buddha had thus hit the citadels of Hindu norms and beliefs where it hurt them most. And, for all that he did to demolish the well-nurtured and cherished Hindu beliefs and institutions, he would be made to suffer sooner or later.

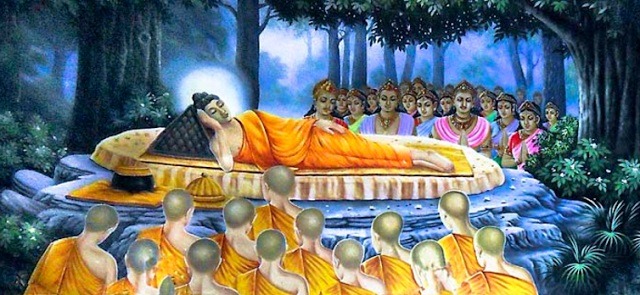

This Hindu-Buddhist tug-of-war is brought into sharp focus even by the composition of the devotees and mourners gathered to collect the Master’s relics. We hear of representatives from Rajagriha, the Lichchhavis of Vaisali, the Shakyas of Kapilvastu, the Bulis of Alkappa, the Mallas of Pawa and the Koliyas. Similarly, amongst the people who set up “Stupas” to preserve the Master’s relics were the Mauryas of Pippalivana, the Nagas of Kalinga and the people of far-away Kandahar. But representatives of most Hindu principalities (except one Hindu priest, Drona, and another Brahmin from Banadwipa) were conspicuous by their absence.

About Buddha’s death itself, which took place in completely mysterious circumstances, this much is known: he had taken shelter in the house of one Chunda, a blacksmith. There he was treated with a dish containing Sukar Mardava, which is said to have brought about his end. One school of thought holds the view that “Sukar Mardava” was a kind of Mushroom, perhaps of the poisonous variety. The other holds that it was pork (ham or bacon).

An advocate of non-violence throughout his long religious career, Buddha may well have abhorred pork at all costs, except by mistake. What therefore, he ate at the house of Chunda was more likely a dish of Mushroom, either poisoned or naturally poisonous. The question should now be: if they were poisoned, how far was it intentional; and secondly, had it been intentional, was Chunda’s a lonely sadistic hand in the apparent conspiracy or was he just a tool at the hands of powerful enemies of Buddha-conspiring to take his life?

Part of the answer may be gleaned from the proceedings of the First Buddhist Council following the Master’s death, where, conspicuous by his absence at least at the initial stages, was Ananda, the otherwise well-known life-long friend and favorite disciple of Buddha, who according to Delva Tibetan Scriptural sources, was later charge-sheeted on seven points, three of which were as follows:

That Ananda had refused water to the Buddha even as the Master lay dying of thirst and requested Ananda thrice for it;

That immediately after Buddha breathed his last, Ananda disrobed him and exposed his naked corpse, including his genitals, to public view; and

That, while wrapping the coffin for cremation, Ananda had disrespectfully stepped on the Master’s body.

It is also said that Ananda had been struck with apparent remorse after the Master’s death. What precise reasons led Ananda to weep over his “doings”, we are not sure. Was it that he had been in the know of the conspiracy, had there been one, even if he had no hand in it himself? The following words of the dying Buddha, addressed to repentant Ananda, reverberate in our memory with a resounding note:

“Ananda, futile it is to weep over me. Whatever is born in this world is destined to death and destruction…I hope you will also rise above petty interests and may one day attain salvation”…

Not only this; the Council is also understood to have awarded a very severe punishment to one Channa, a charioteer of Buddha, with what in those days was known as Brahma Danda, besides expelling him from the society of the Buddhists. This step taken by the Council also leads us to strongly suspect Channa’s role in that mysterious affair was not above board.

Agreed that all this is legend. Agreed also that legends do not make history, as history has to have the sanctifying touch of evidence, such as epigraphy. Our story has no such sanction behind it. But how about the contrary version-the version of a natural death? What do we have but the historian’s word for it-and mere word at that?