Mahesh Paudyal

Gopal Parajuli’s persistent engagement with death as a theme of poetry has become his poetic trademark. Death, in reference to his poetry, should not be understood merely as end of life. It is a constant antithesis of the presence of life; it is a nemesis to the light of life. Death, as his artistic polemics claim, is much weaker than commitment to live and let others live. It is beatable with the bludgeon of life force.

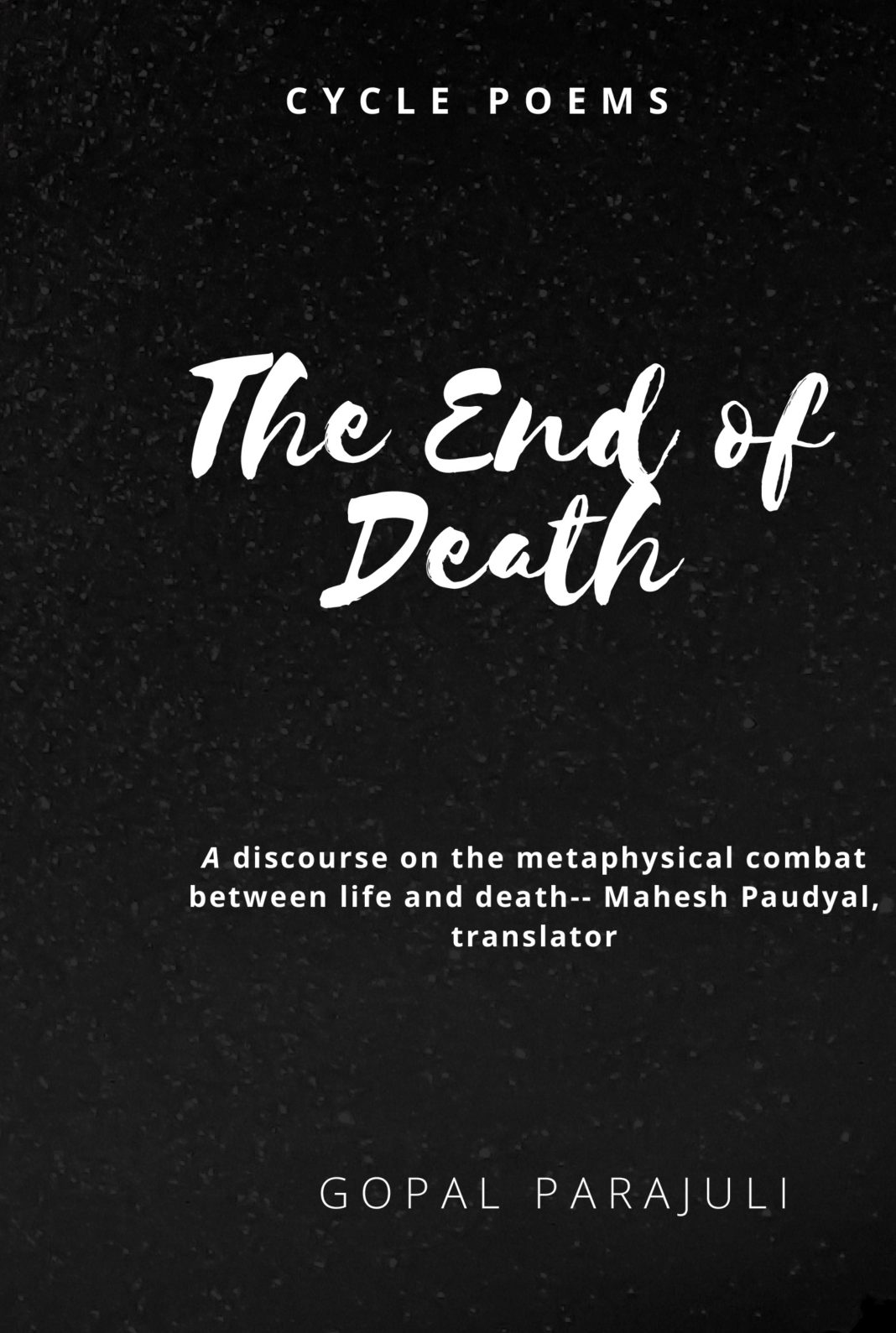

This is where a reader arrives after a serious recourse through Poet Parajuli’s latest collection of poems: The End of Death. Published by Amazon.com, the anthology has eighty-four poems, each of which is an independent poem when read in isolation, but a member in a thematic sequence, when read as a part of a larger sequential scheme of thematically connected poems. Named ‘cycle poems’, these individual yet connected poems are yet another bead in the sequence of relentless experimentation poet Parajuli is famous for.

The End of Death is an encapsulated discourse on the metaphysical combat between life and death. Life, for which the poet votes, is an uninterrupted force of existence that prevails even after the end of physical body, and thus transcends the quicksand of death. Poet Parajuli has, in these ‘cycle’ poems, acknowledged the immortality of soul governed by conscience. In tune with the Eastern philosophical belief system, poet Parajuli cites the imperative for the soul to stand with righteous thoughts and actions for a guaranteed prevalence over death. A righteous soul that shuns arms, wars and violence, and sides with peace, humanity and love, ultimately beats death and comes out victorious. In order to plead his theme, the poet has acknowledged the contributions of great personages—deities, poets, prophets, peace workers, intellectuals, leaders and philosophers—who have secured the world from the claws of death during their lifetime. In his parent experimental style, run-on lines, prose without punctuations and first personal and partly confessional mode, Poet Parajuli has made a global appeal for peace and righteous actions as crucial for the future of the universe.

The entire vantage is human; man’s worthy life is the ultimate pursuance of the poet. He imagines a righteous world in which man explores all potential to qualify to the rank of God, and shuns every petty thing that questions the very wroth of humankind. The poet confesses that man today is ‘in a labyrinth of arms’ right from the day of his birth. Beyond the visible labyrinth of threats, nuisances and disturbances is yet another labyrinth—that of death—making the presence of labyrinths a cyclic reality. The philosophy on which these poems hinge is that idea of transcendence, according to which, it is possible for ordinary mortals to assume a persistent ascent from ordinariness to extraordinariness and qualify to the rank of divinity, the way Prince Siddhartha became the Buddha. This approach to transcendence, the poet imagines, is an attempt of an individual to become a part of the Creator, an emblem of permanence. This idea is on consonance with the Eastern philosophical claim that the Creator, also referred to as Paramatma or the Oversoul, is the ultimate conglomeration of all individual souls that escape the labyrinth of life-death cycles, and ultimately attain moksha or salvation through their integration with the Creator.

How the poems have been arrayed can be best understood from the poet’s own clarification. He writes: “This experiment with cycle poems, arrayed with an interdisciplinary approach, is in the process of forward motion, signaling the future time that the present shall find no repose by tagging itself with the past. Man is mortal. This is a blatant truth. But there also is a different truth. The Creator is immortal. It is necessary for all of us to fight with death. Man is inside a cycle of wars. Time plays it own tricks, though it cannot put life to an end. Life takes off and lands. The cycle continues.”

In order to play his theme, the poet has used a comprehensive array of instances, anecdotes and images. Both from the Eastern and Western worlds, he has acknowledged the transformational evolution of people from ordinariness to extraordinariness, and poetically speaking, from mortality to immortality. As counterpoint to his argument, he has also mentioned names, who were a threat to the existence of the human being. He has questioned the ontological relevance of terrorists, their organizations, dictators, tyrants and miscreants, who have during their days ripped the human kind with threat and violence. The poet has also incorporated intimate family experiences—with this son, daughters, wife and close relatives—to suggest that idea that in a close-knit relational web, death of an individual does not remain an individual case; it assumes a collective relevance. The close-knit family intimacy has also been projected as a shield against the impertinent approach of death.

The poet has invented Prakash, literally ‘light’, as the human embodiment of transcendence. The ultimate motif of his entire pursuit seems the discovery of Prakash, and hence, the discovery of a penance against death. He writes:

Moksha liberates the cycle of death

God is there in someone’s hand

Where death alights

To which place one’s heart is drifted

And where one’s dress is flung

That is where the world lies

That is where Prakash exists

(Hands inside a Closed Room)

The constant defeat of truth, man’s avarice and greed for power, and denial of the acknowledgement of divinity are some of the reasons the poet identifies for the burgeoning of violence and falsity in the world. From a myriad of sources including mythology, history and literature, he has cited dozens of characters, whose petty selfishness has pushed the world into the murky pit of death and destruction. Re-kindling the light of divinity in the humankind and reestablishment of God in an individual, the poet thinks, will restore the world to its erstwhile innocence, and secure humanity from the clutches of invented death. The physical existence may naturally end, but an exit after a glorious and healing presence does not sum up to death. Instead, it is a defeat of death and an entry towards permanence.

***