TGT Desk

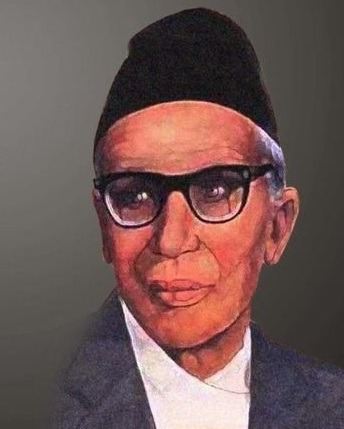

Since poet Siddhicharan Shrestha lived at a politically volatile time, he obviously had great political connections, both as a friend and as a foe. For going voice to revolutionary idea, he was an eyesore to the Rana rulers of his days, who announced imprisonment as punishment for his anti-state views. Revolutionaries, on the other hand, championed his call for freedom, because his slogan, “There is no peace without revolution” carried the spirit of his days.

Various top-seeded political leaders of Nepal have expressed their views on the great poet Siddhicharan. This article carries some of the representative viewpoints. The statements have been extracted from the book Great Poet Siddhicharan, published by Yugakavi Siddhicharan Shrestha recently on the occasion of the poets’ birth centenary.

Bir Ganeshman acknowledges Siddhicharan’s direct influence upon his political spirit during their stay together in the jail. He writes: “In the context of Nepal’s political revolutionary sensibility, I myself was impressed by Siddhicharan dai’s poetic personality and his individuality, and how he unhesitatingly became involved in political life. I was also one of the rebelling youths who would murmur and sing his revolutionary poetry. I can still recite most of his poems by heart.”

Matrika Prasad Koirala loves to remember Siddhicharan as a volcano of a placid make. He remembers the mid thirties when his family had walked into Kathmandu valley as non-residential citizens. It was then when Siddhicharan had given life to Sharada, the first literary magazine of Nepal. Koirala was brought into Siddhicharan’s company by author Bhavani Bhikshu, who had a distant relation with the Koiralas. This is how late Koirala remembers his first meeting with the poet: “In our first meeting I did not get any glimpse of the fact that placid and decent Siddhicharan was developing into a revolutionary flame. But as our relations grew closer, I could witness more of the storm and heat of revolution inside him.”

Kedarman Vyathit, former minister and Chancellor of the then Nepal Royal Academy met the poet in jail, when both were confined for anti-Rana moves. Vyathit recalls their meeting and admits that it was Siddhicharan who inspired him to write poetry. He commemorates: “Siddhicharan is a free-flowing cascade that doesn’t have to exercise skills of craftsmanship while writing poetry. While making the description of society and nature, he does so in the tempo of a cascade whose foundation never dries.

Former Prime Minister Man Mohan Adhikari sees Siddhicharan as a revolutionary poet. In one of his commemoration, he writes of an incident when he needed Siddhicharan’s moral support in the people’s movement of 1950. Recalling one of their meetings, he quotes Siddhicharan as saying, “The youths and the politicians should take the lead march for social change. We the writers too will join, but we are just means. We the litterateurs shall make public opinion; you the politicians must lend it a leadership.”

Happy with the poet’s ardent and unconditional support, Adhikari reveres him with high esteem and compares him with PB Shelley and John Keats of England. He writes: “Siddhicharan Shrestha is in no way inferior to Shelley and Keats. In the parliament elected after the reinstatement of democracy, I have always been pleading in favour of honouring such a national luminary, and translating and dissipating his works abroad, and ever since, I have continued to do so.”

Former minister Sahana Pradhan remembers Siddhicharan as an inspiring force behind many of the revolutionaries including Pushpalal and Ganga Lal. She writes: “He is in fact the embodiment of the climax of anti-Rana movement. He is one known for nature poetry and for revolutionary literature together. He was a simple man with simple heart. Simplicity and ideological genuineness are his qualities.”

Sahana’s writing reveals that she came to know of him only after the movement of 1950. After 1960, whenever Pushpalal sent letters from exile, she would carry them to the poet. The poet and Pushpapal would correspond very frequently. After the referendum, she would frequently visit the poet, and during those visits, she came to have the glimpse of his greatness as a revolutionary poet. She writes: “The poet’s position in Nepali literature is no less than that of William Wordsworth in English literature. To be even more precise, while Wordsworth confined himself to writing about Nature, poet Siddhicharan transgressed the boundary to address issues concerning politics and social change in his literature.”

Former Prime Minister Kirtinidhi Bista recalls some of his memorable time with the late poet: “I have had the privilege of being intimately associated with poet Siddhicharan and closely observing his human and poetic qualities and talents. He was a sincere person of pure and spotless character.”

To Modanath Prashrit, former minister and author, Siddhicharan ushered in the first ray of Romantic poetry in Nepali literature. His poem ‘Pratakalin Kiran’ that appeared in Sharada in 1934 was “the first ray towards Romantic cult in Nepali poetry.” He also remembers Shrestha as the first poet to talk of the New Nepal that has become the political buzzword of these days. He adds: “Mainly because of his extraordinary power to express the awareness of time and national consciousness more powerfully than any of his contemporaries, Siddhicharan was rightly called Yugkavi by the then intellectuals and authors.”